You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘powerdown/post peak oil’ category.

This post is part of the UK Herbarium blog party Gems from the Herbal Library.

When I was young, like many of that age I loved dyeing clothing. There was a magic in the transformation of an old favourite or a new opshop find simply by immersing it in coloured water. As a teen I used Dylon dyes, bought in wee metal containers from the supermarket or chemist. They were easy to use, affordable and perfect for teenage experiments. I remember the excitement when we discovered Dygon, the chemical that stripped existing colour from most cloth so it could be redyed in the colour of our choice. In my early twenties I moved on to procion dyes and screen printing, both giving me a much wider range of things to experiment and play with.

Somewhere in all that I remember collecting dandelions from the lawn of one memorable flat – the lawn was completely covered in brilliant yellow blossoms and I was sure there must be a way to get that brilliance into cloth. I don’t remember the technique I used, but the results were disappointing. The reading I did at the the time and the people I consulted all seemed to be saying that wool was relatively easy to dye, but cotton wasn’t, and either still needed chemicals of varying degrees of toxicity to make the dye take. I was already finding the procion dyes and screen printing chemicals came with impacts on human health and then when it dawned on me that those dyebaths and cleanup chemicals we were pouring down the drain at the end of the day had to actually go somewhere… well it was easiest to just stop. Occasionally I would read up some more on using plants to dye with, but it still seemed that overly toxic chemicals were needed and I could never reconcile that with the idea that people have made beautiful clothing for eons before we had those chemicals.

So it’s been my utter delight to discover the work of India Flint and other natural dye artists. Flint is an Australasian* fibre artist who has been working with plant dyes for twenty years, building up an impressive body of knowledge on what works and what we can experiment and play with successfully. What makes her work so exciting is the low level of toxicity of the substances she uses (many can be found in the kitchen), and her ecological sensibility – we can have beautiful fabric and clothing without damaging the land.

*Born and living in Australia but has connections into NZ and a deep understanding of the land here.

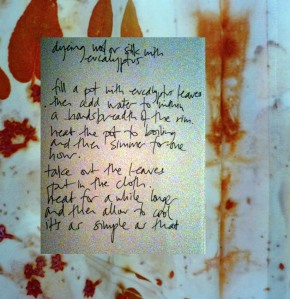

Flint has pioneered ‘eco-printing‘ on fabrics (using plants), and has specialised in the dye properties of many of Australia’s eucalypts (animal fibres will take eucalypt dyes without the need for any mordant).

The book Eco Colour is both a showcase of natural dyeing and an instructive on how to. A large format book, it’s is beautifully presented, with copious colour photos. These include examples of Flint’s work, the plants and the processes.

Flint has a clear communication of the problems with chemical dying – from the effect of what goes down the drain, to the impact on the dyer, and the impact on the wearer of having chemicals next to our skins (I can still sometimes pick the smell of dygon-like chemicals on commercial clothing that has obviously been through a predying process, especially wool).

I also love her ecological sensibility. On the issue of colourfastness, where commercial dyes are meant to last years and so strong, very toxic chemicals are used to achieve this, she advises that if naturally dyed cloth fades, you can simply re-dye it. For those of us that love simplicity and the magic of the dying process this is perfect.

Perhaps closest to my heart is the concept of bioregionalism. I’m a bioregional herbalist (I believe that most of our medicine can come from where we live) and Flint focusses on dying with the plants that grow around her. It’s hard to describe the importance of this sometimes, but on an obvious, practical, post-peak oil level the skill to create beauty from our landbase is invaluable.

More than that though, bioregionalism takes us into such a direct relationship with the land that it becomes impossible to not see the connections between the land, ourselves and how we treat the world. Flint’s work demonstrates and reflects that relationship, for which I am profoundly grateful. It’s not just the ability to craft fabric without excessive chemical use, it’s that the craft, the art and the play are taken back to their natural source in the land, and so are we.

In more practical terms Flint outlines many techniques: how to prepare dyes, the various mordants and what they can be used on, how time affects the process, the plants themselves and the colours they yield, health and safety (natural dyes and mordants need careful handling too), how the metal of the dyepot or resist can change colour etc. This is probably not the best book for an absolute beginner – it helps to know what a mordant is for instance, and basic dyeing techniques. Flint does explain each concept and technique as she goes, but she doesn’t give actual recipes. Natural dyes can be used by beginners more easily than harsh chemical dyes, so Eco Colour would sit well alongside a basic dyeing primer for those not used to the techniques (try the internet or library).

Many of the substances used in natural dyeing can be found at home or in the supermarket – soda, vinegar, milk – and Flint explains how these can be disposed of at the end of the dye-ing process. She also introduces the basic chemistries involved.

Although she has done extensive work with the native eucalypts, most of the plants in the book are common in many parts of the world. Further, the techniques are imminently transferable to any plant. I’m already eye-ing up plants in my neighbourhood wondering what dye would result.

There is an abundance of techniques to try out, ranging from the simple and known ordinary dye baths to the intriguing (ice dyeing) and the even more intriguing (compost dyeing). Flint intersperses the book with historical accounts, both from her own life and family traditions, her natural dyeing antecedents, and general plant dyeing background.

There are many things here to delight the herbalist. Flint talks about how plants high in alkaloids can be used as mordants and notes that many medicinal herbs will be useful in dyeing because of this. Tannin rich plants is the other obvious one.

I should point out that I’m not an artist. I have some craft skills but my experiments with plant dyes are mostly for practical purposes – how to transform the colour and look of fibre and cloth in ecologically sensitive ways, so that I can use them in my own life. While Flint is an artist and the book is for the artist’s eye, the techniques in the book are adaptable for more mundane projects too.

India Flint has a blog, and there are links there to other natural dyers the world over. Eco Colour is available from many online booksellers, and in NZ it’s also available in libraries (by interloan if your local doesn’t have it). Amazon in the UK has a Look Inside! preview that doesn’t do justice to the visual splendour of the book but does show the contents, index and introduction. Flint also travels extensively giving workshops.

I’m currently reacquainting myself with stinging nettle. For many years I made nettle leaf infusions, and then my body and tastes changed and I haven’t used it for a long time. Now with the wet spring there are nettles everywhere I go, so it’s hard not to be thinking about medicine again. I’ll do some posts about nettle as food and medicine, but first I want to talk about the plants themselves.

We have a handful of nettle species here in NZ, most are native and several are introduced.

native:

Urtica ferox, ongaonga, tree nettle: endemic (grows only in NZ).

Urtica incisa, dwarf bush nettle, scrub nettle: non-endemic (grows in Australia too).

Urtica linearifolia, swamp nettle: endemic.

Urtica aspera, grows in the South Island: endemic, rare.

Urtica australis (aka U aucklandica) ongaonga/okaoka, onga, taraongaonga, taraonga (I’m guessing the number of Maori names is due to the mix of Northern, Southern and Chatham Island dialects), Southern nettle: endemic, rare, found in coastal Fiordland, Stewart Island, the Chathams and the sub-Antarctics. Originally grew as far north as the bottom of the North Island (probably).

introduced:

Urtica urens, stinging nettle, small nettle, nettle: common throughout most of NZ, but uncommon in places (West Coast, Fordland, Taranaki, North Auckland).

Urtica dioica and subsp gracilis, stinging nettle, perennial nettle, tall nettle: uncommon.

Urtica membranacea, a Mediterranean nettle: I’ve not seen it but it’s listed as naturalised in Canterbury at least.

I’m going to write about the most common species. Nettles are plants of the disturbed ground. They grow in places where the soil has been bared, and so are common along roadsides, tracks and where land is overgrazed or otherwise cleared. Nettles love nitrogen and grow in places where the nitrogen is very high eg animal manure. I suspect that nettles play a crucial role in breaking down animal manure in places where the soil is marginal and struggling to re-establish other plants.

Nettles are most notable to the general public for the hairs on leaves and stalks that sting, sometimes quite painfully. Nettles are good medicine and food (being very dense in nutrients), and are useful in the garden and for fibre. As such they are another important plant to know well in preparing for the powerdown/post peak oil future.

Urtica urens is our most common weed nettle and was introduced in the 1800s, most likely from the UK (first recorded in NZ in 1860). It’s an annual, grows in disturbed soils, and seems to especially like sheep shit. I find it most often under and around stands of trees that sheep like to shelter under (manuka, kanuka, pine etc) but it will also sometimes grow in the open where the rabbits have been digging or where the soil has been disturbed in another way. My ex-neighbour always had a great crop of annual nettles in her garden because of the chicken manure and digging. Unlike some of the other nettles, urens has an affinity for dry ground.

Urens will often grow on a single stalk, but it can also grow multiple stalks and fan out into a small bush. It is a darker green than the other nettles (getting darker as it ages) and has a more rounded and textured leaf than the perennial. It’s sting is less painful than the perennial nettle but it has more stings and on both sides of the leaf (as well as the stalk). Most of the references you see to nettle as a medicine and food are not to this plant (more on that in a later post). They’re to its sister the perennial nettle:

Urtica dioica, a perennial nettle, was also introduced in the 1800s. It’s uncommon enough in NZ that I’ve never seen it growing wild, despite looking hard. In the US people talk about it growing near water. It has a pointier leaf than the annual nettle and looks similar to lemon balm in shape.

Unlike the annual, the stings on the perennial are predominantly on the top of the leaf, which is why some daring folk will eat them raw.

It’s considered a pest plant in NZ (what used to be called a noxious weed), mainly because its strong, spreading root structure can be difficult to contain once established. In some parts of NZ it’s illegal to distribute any part of this plant, so be careful, eh? If you want to grow it best to plant it somewhere reasonably contained like you would mint.

Urtica ferox, aka ongaonga/tree nettle, is one staunch plant. This native is large – up to several metres high, and grows in the bush, especially along margins of river and roads or in clearings. It also grows on farm land, having that same affinity for sheep shit and cleared land, but unlike the annual nettle (Urens) it often grows well out in the open.

The sting of this native is so strong that bad enough exposure can kill horses (eg where horses have been ridden through a stand of ongaonga. Humans too, but that’s incredibly rare. The sting is much worse than ordinary stinging nettle, and contact from even a single hair can be very painful for hours.

Urtica incisa and Urtica australis both have the potential to be useful as medicine if cultivated or reintroduced into native or non-native ecosystems and gardens. The seed of both those native nettles is available on Trade Me if you want to try them out, and the plants are available from Oratia Native Plant Nursery (as well as ongaonga).

Incisa I’ve seen in the bush and it’s always quite small so I’ve chosen not to harvest it (better to leave it for the bush anyway), but it would probably grow bigger in a garden (descriptions of the plant in Australia are much bigger than the ones here). I always see it growing near creeks so it’s one of the wet footed nettles.

The Chatham Island nettle (U australis) in particular looks interesting with its large heart shaped leaves (one report says they’ll grow as large as a lunch plate). It’s a perennial which means you can harvest the plant and it will regrow another crop. I don’t know how bad its sting is but online sources suggest its milder than most nettles.

All the nettles are becoming popular in NZ gardens because nettle is a prime food for the caterpillar of the Monarch and Red Admiral/kahukura butterflies.